From an economic development perspective, Ottawa is currently undergoing a massive and mostly promising transformation. From the construction of the new light-rail line to Kanata’s experiment as a testing centre for self-driving cars to the redevelopment of LeBreton Flats, Ottawa is clearly a city that is looking optimistically and confidently to the future.

In addition to boasting a world-class high-tech sector, Ottawa has carved a niche for itself as a centre of innovation in the areas of post-secondary education, health care and the administration of local government services. On top of this, the city is consistently recognized both nationally and internationally as providing an extremely high quality of life, a fact which helps drive both immigrants and Canadians from other cities to the Ottawa area.

Unlike some other large Canadian cities such as Calgary, Ottawa remains relatively diversified in terms of its economic drivers (a point that helps to somewhat buffer the city from fluctuations in any specific industry), and the city has mercifully avoided the insanity that has gripped the housing markets of Vancouver and Toronto. These facts all help to paint a rosy picture for the future of economic development in the nation’s capital.

(Sponsored)

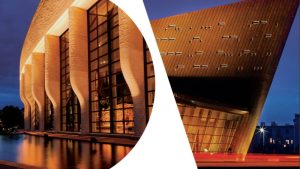

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

OCOBIA eyes Ottawa BIA expansion as it gears up for election year

Michelle Groulx says it’s not difficult to spot the Ottawa neighbourhoods with their own business improvement area (BIA). That’s because, she says, BIAs are a visual and experiential representation of

Yet despite such strengths, a cloud hangs over the future of the city’s economic development prospects.

Economic development diversity

Like many medium and large cities, Ottawa suffers from a clear saturation of economic development actors, each working with their own mandate and towards their own ends. From Ottawa Tourism to Invest Ottawa to the City of Ottawa’s own economic development and planning specialists, the cast of characters in this process is both numerous and diverse in terms of management, style, budget and goals. And these are just the organizations that are directly connected to City Hall.

On top of this, we can add the various organizations that function mostly independently but which are still connected to city government on some level, such as the various business improvement associations (BIAs) and certain well-connected community and neighbourhood associations.

And finally, there are the actors that are completely separate from the City of Ottawa but which push their own vision for local economic development, such as the three main local business advocacy groups (the Ottawa Chamber of Commerce, West Ottawa Board of Trade and Orléans Chamber of Commerce), land development companies, citizens’ groups and special-interest advocacy organizations engaged in a wide variety of activities, and which may or may not have a strong influence on local political decisions.

While not all of these actors are concerned directly with economic development in the sense that most readers of this publication might define the concept, they are in almost every case pushing a vision that will impact somehow on Ottawa’s economic prospects.

While Ottawa’s situation in this regard is certainly not unique, it is nonetheless problematic.

It might be argued that having a variety of stakeholders each working separately can help to bring a certain diversity and liveliness to the process of economic development, and there is, of course, some truth to this. This concept does, after all, define the nature of a democratic society, and it therefore makes perfect sense to have several different actors each pushing their own agenda, a process which hopefully leads to some level of consensus-building.

But this is perhaps where Ottawa is somewhat atypical of a Canadian city. Rather than a cacophony of competing voices (such as exists in Toronto or Vancouver), economic development in the nation’s capital is surprisingly sanguine, with most voices agreeing on at least four fundamental areas: firstly, that a net inflow of population is positive (and that this net inflow is directly tied to the image non-Ottawans have of the city); secondly, that everyone benefits when the business sector is strong; thirdly, that Ottawa has the potential to be one of the greatest medium-sized cities in the world; and finally, that in order to achieve a certain level of greatness, investments must continue to be made in developing the city’s economic resources, be they social, financial, cultural or physical.

Duplication

In my experience, there is almost universal agreement on these four points, and this is undoubtedly one of Ottawa’s great advantages in terms of economic development.

At the same time, this also means there is a great deal of duplication in terms of planning, administration, resources and goals. This is so true that, in some cases, it is difficult for the average observer to detect any real differences in mandate between certain organizations, despite the strong work done by these respective groups.

In the past year or so, a commendable effort has been made to address this issue by bringing the various stakeholders together via the informally titled “G33” working group – a collection of organizations that meets infrequently to discuss priorities, share experiences and develop a common set of assumptions and goals around economic development in Ottawa.

While it’s unclear to what extent this working group has really led to any great improvement, it seems clear that the city’s various economic stakeholders are all equally committed to working together and building a more collaborative environment. It’s also the only real venue where decision-makers from organizations as diverse as Algonquin College, Invest Ottawa and Ottawa Tourism can formally meet to discuss plans, outlooks and goals. On top of that, the “G33” is a clear example of City Hall’s seriousness about the task of building a stronger local economy.

Ottawa is in a unique and largely fortunate position. While the city may be struggling to define a common agenda across its various economic development actors, and while these actors may not yet have developed a distinctive voice in regards to building a more vibrant economy, at least our city doesn’t suffer from a lack of engagement in this area.

As technology and globalization continue to reshape the purpose and collective minds of urban centres across the country, the challenge in the future will be to ensure that Ottawa’s various economic development actors can work together in the most efficient and productive way possible. An Ottawa that can truly embrace collaboration among its diverse economic actors will be strongly positioned to navigate the dynamics of both global and local change for years to come.

Mischa Kaplan is a local business owner and part-time professor in Algonquin College’s School of Business. He is also the second vice-chair of the West Ottawa Board of Trade and a member of the Ottawa Chamber of Commerce’s economic development committee.