Moe Abbas saw the same problem with a lot of the talent that was joining his startup team, Bumpn. Namely, the graduates he hired were coming to him straight from university programs, unskilled and unprepared for the modern workforce.

“We were hiring all of these interns and we were just spending so much of our time training them,” Mr. Abbas recalled in an interview with the Ottawa Business Journal. He says he realized then how unproductive it was to train and integrate new interns and employees. That lost time drastically lowered the value of his hires.

The Ottawa Business Journal found similar sentiments from company executives in its business growth survey earlier this year. Forty-seven per cent of surveyed Ottawa business owners and executives cited “skilled workforce” among the three biggest issues facing their companies.

(Sponsored)

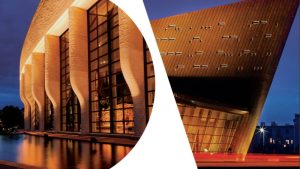

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

The story behind Glenview Homes’ 2025 GOHBA award-winning Reveli floor plan

When Glenview Homes’ Design and Drafting Manager Eno Reveli sat down to design a new production floor plan, he wasn’t thinking about awards or show homes. He was thinking about

Looking at this gap, Mr. Abbas saw opportunity.

His new startup, GenM is aimed at providing training for the millennial generation. In its current phase, GenM is a one-player software-as-a-service solution to provide clients with in-demand marketing skills through project-based learning. Candidates work through step-by-step modules doing sample projects common to real-world companies that are then reviewed by GenM.

Clients can either do single projects or work through a full “M Degree,” which, upon completion, certifies the candidate in GenM’s view as capable of performing a role like social media specialist.

Mr. Abbas says this approach can take students with generalized degrees such as psychology or literature and train them in the skills they need to break into the job market.

“The education system has not evolved, yet the workplace has,” he says. “We’re fixing the skills gap between education and employment.”

Getting off the ground

GenM launched early in September and, according to Mr. Abbas, has quickly found success. The company drew initial investment from friends and family, and is already seeing revenues from early adopters.

Mr. Abbas says demand is “ridiculous,” so much so that the company has stopped onboarding users for the near-future. Instead of making a mad grab for clients and ending up with a high turnover, GenM’s priority is to perfect the formula for getting users to complete projects. Then, and only then, will the company launch a full-fledged campaign for clients.

“You make a promise, you want to fulfill that promise… I don’t believe in scaling a company until you really line up your metrics,” says Mr. Abbas.

Long-term obstacles

Mr. Abbas has a number of ideas for GenM’s potential. After graduating candidates from the M Degree program, he’d like to reintegrate them into the product through a peer-to-peer mentoring system, and he sees a future for GenM as a learning management system that companies use for training internally. The big goal, however, is to bring external companies into the solution.

“Our big vision is to bridge companies into the education system,” Mr. Abbas says.

The idea is that eventually companies could submit their own projects to the GenM system to be completed by a candidate in-training. GenM clients wouldn’t be paid for their labour, but Mr. Abbas says that there’s a value in the potential connections and portfolio pieces that will come from working on real-world projects.

He believes GenM will be able to make this work, but Ontario’s labour laws surrounding unpaid work are limiting.

Based on OBJ’s description and an inspection of the GenM website, Andrew Langille, general counsel for the Canadian Intern Association, says the company’s proposed model raises questions.

“If they were to get people who enrolled into their M Degree program to do actual work on behalf of businesses, it would be illegal under the Employment Standards Act 2000,” Mr. Langille told the Ottawa Business Journal in an interview.

Under the act, there is a section to allow for unpaid internships that lays out six conditions to be met in order for a program to qualify. Mr. Langille says that one such standard, “The employer derives little, if any, benefit from the activity of the intern while he or she is being trained,” is notoriously difficult to meet.

Mr. Abbas claims that because these projects are so short (between one and 10 hours of work), companies are deriving little benefit from the program. But Mr. Langille says that any benefit whatsoever, under current case law from the Ontario Labour Relations Board, is illegal.

“I’ve structured programs for employers before, on this part of the ESA. It is extremely difficult to meet. It’s almost impossible to meet. There’s a huge amount of hoops that you have to jump through,” he says.

After the initial publication of this article, Mr. Abbas clarified that GenM is not currently enabling businesses to post projects. He told OBJ that he has been in contact with the Ministry of Labour about this coming-phase of the business, and will “consult with all relevant authorities to ensure projects comply with ESA standards.”

Mr. Langille has other concerns with what he has observed from GenM, including an unsubstantiated claim on its website that their M Degrees are “recognized by industry leaders.”

Mr. Abbas says the claim is based on numerous conversations he has had with CEOs, but adds that what employers will care most about is the quality of the work candidates will be able to showcase.