As Ontario municipalities enact new measures regarding the use of masks in commercial locations, business owners are on their own when it comes to dealing with customers who refuse to comply.

On Tuesday, Ottawa and Toronto joined Kingston in establishing rules requiring a non-medical face covering inside businesses that are open to the public.

Under the rules, businesses are responsible for making sure customers wear a mask, and face fines for failing to display and enforce their mask policy. However, short of calling the police on noncompliant customers, businesses may find they have little power to enforce their policies on the public.

(Sponsored)

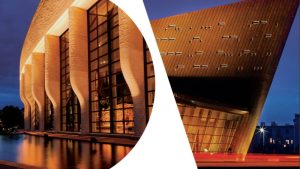

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

The story behind Glenview Homes’ 2025 GOHBA award-winning Reveli floor plan

When Glenview Homes’ Design and Drafting Manager Eno Reveli sat down to design a new production floor plan, he wasn’t thinking about awards or show homes. He was thinking about

One scenario facing business owners is the possibility that an anti-mask activist will try to enter without a mask. Recent videos circulating on social media have depicted people trying to enter Toronto-area stores or hospitals without masks. In some videos, customers threaten legal action.

Children under the age of two and people with certain health conditions are exempt from the condition to wear masks, and no medical proof is required to claim that exemption. Ottawa Public Health has said its policy, which came into effect Tuesday, “will be enacted and enforced in good faith and will be primarily used as a means to educate people on mandatory mask use in enclosed public spaces.”

According to Michelle Flannery, corporate communications officer with Toronto Police Services, a business can direct a person to leave under the Trespass to Property Act, and that “ultimately, if anyone were to feel their safety was in jeopardy, they should always reach out to police” or dial 911 in emergencies.

“The establishment could refuse to serve this person,” said Cara Zwibel, a lawyer with the Canadian Civil Liberties Association. “They probably could contact law enforcement and deal with it as a trespass. I certainly don’t think that’s something that we should be doing, but that’s not precluded by the bylaw.

“The truth is that power, subject to the human rights code, existed before, anyway. You can’t refuse service on a protected ground. Otherwise, there is the freedom to contract who you want to – and the freedom not to contract with who you don’t want.”

Ontario Premier Doug Ford has previously said the province lacks the capacity to enforce mask bylaws.

Businesses, meanwhile, are left to enforce what the Retail Council of Canada called a burdensome patchwork of municipal policies. Businesses with multiple locations may find they are obligated to ask maskless customers to leave in some cities, but not in others, the council said.

Toronto employment lawyer Nadia Zaman noted employers are not only charged with protecting consumers’ human rights, but also providing safe workplaces for their employees, who may be concerned with enforcing the new rules.

“If someone says, ‘You can’t impose this on me,’ it’s not as if the rights of the customer – even if they were to fall under the exemptions – are going to be absolute. There are situations where there are competing rights in place,” she says. “Does this result in undue hardship, in the sense that it poses significant health and safety risk to workers? That is not assessed in a silo.”

Zaman says she encourages businesses to document any enforcement interactions so they do not forget the details of how the policy was explained to the customer. She added that employees should be given frequent options to raise any incidents that concern them.

Managers could consider formalizing an alternative way to provide service to someone without a mask – such as providing them with a mask, putting employees behind barriers or slowing the influx of customers to allow six feet of distance, says Zaman.

Zaman cautioned that if a customer refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons, businesses cannot ask for proof of an exemption, as doing so could trigger a human rights complaint if the person suffers from a disability.

Those who claim to be exempt due to medical conditions should be accommodated, says Zaman, unless accommodation would cause undue hardship on the business owner. If a business does face a complaint, it can be difficult to prove undue hardship before a human rights tribunal, although it is possible, says Zaman.

Zwibel says that putting the onus of enforcement on commercial establishments puts businesses in a difficult position, but that may be necessary to help usher in a major behavioural shift for consumers. Exemptions for medical conditions, and bylaws focusing on education rather than punishment, could be designed to diffuse potential conflicts, says Zwibel.

“No one should be asked to prove that they can benefit from an exemption. If you are asked in a store whether you are exempt from wearing a mask, and you say yes, there’s nothing else that a store should be doing. You should be taken at your word,” Zwibel says.