Wanda Cotie is no stranger to the challenges and darkness of this world. As the owner of Wicked Wanda’s Adult Emporium and an advocate for creating “safe places,” Cotie says she “sees so many people’s stories.”

Now, she’s sounding the alarm over Ottawa’s homelessness and addiction crisis that she says has become all too commonplace.

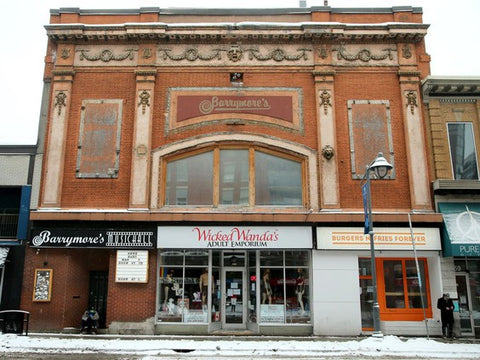

Wicked Wanda’s moved from the west-end community of Britannia in 2009 when a fire destroyed the plaza in which it was located and relocated to a storefront on Bank Street in Centretown.

(Sponsored)

Powered by passion, backed by Ontario Made: Turning bold ideas into entrepreneurial success

Back in the winter of 2018, a brutal cold snap dropped temperatures in Merrickville to -46°C. Michael J. Bainbridge and Brigitte Gall looked outside and told their holiday visitors to

OCOBIA eyes Ottawa BIA expansion as it gears up for election year

Michelle Groulx says it’s not difficult to spot the Ottawa neighbourhoods with their own business improvement area (BIA). That’s because, she says, BIAs are a visual and experiential representation of

“I thought I’d look at the future of Bank Street and invest in the early stages because I believed we’d see a turnaround downtown,” Cotie says. While she had to move across the street from her first location, she decided it was worth the cost. “And then we had a pretty good go until COVID.”

Settled in the Barrymore’s Music Hall building at 323 Bank St., between MacLaren and Gilmour streets, Cotie spent the pandemic working non-stop by herself, amping up online sales and delivering in the Ottawa region. But in the past few years, a methadone clinic opened in the pharmacy across the street and many of the social issues facing Ottawa came right to Cotie’s doorstep.

In the time since the clinic opened, Cotie has seen an increase in drug use and homelessness on her block to an extent that has “traumatized” and “saddened” her. She says it is a crisis that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

She sees narcotics and other street drugs used right on the sidewalk and frequently witnesses people collapse from substance use.

“We watch people overdose all day long; there are people camping there. One man, his name is Curtis, is sleeping near us,” Cotie says. “The ambulances are down in this block over and over again. I’ve had people say, ‘Aren’t you going to do something?’

“I call 911 and they tell me to go over and check for breathing, but I’m scared,” she says. “We stand and talk to them, they’re human beings, and I’m not without sympathy because I know so many people who struggle with addiction, but there’s just no help.”

Cotie has approached some of the people in the past, concerned for their safety, but with increased violence and volatility, she increasingly stays in her store.

“(911) always sends somebody, but by the time you’re talking to 911, most of those people are coming to, confused and sometimes angry and you say, ‘Oh, okay, sorry, I thought you were dead,’” Cotie continues. “It’s pretty traumatizing to watch that. If I wanted to stand outside the door and watch the street, I could see that every day.”

According to data from Ottawa Public Health, opioid overdose-related deaths in Ottawa have risen since the pandemic. The most recent data from the third quarter of 2022 reported 29 deaths, 11 more than the same time in 2017. The City of Ottawa declared a homelessness emergency in 2020 but, according to data from the Ottawa Mission, the number of people living houseless has doubled since then.

Since COVID, Wicked Wanda’s has been robbed and, due to the increased presence of drugs, Cotie’s customers avoid coming to the store in-person.

“It’s just gotten worse and worse. We offer delivery, so I drive it out to the suburbs and sometimes even just to the edge of Centretown because people don’t want to come. It says a lot,” Cotie says. “We used to be open at night so we could catch people who went out to dinner and now we’re closed by 10 o’clock.”

Sales and revenues for Wicked Wanda’s are down 20 per cent from pre-pandemic earnings, Cotie says, largely due to the lack of walk-ins. “People just don’t come to this area for the Bank Street shopping experience anymore,” she explains.

Before entering the sexual wellness industry 25 years ago, Cotie had a career in real estate. She says she sees a need for “safe spaces” for people to recover in areas of the city that make sense. She suggests using downtown office buildings that are “sitting empty” while people live houseless just outside the doors.

“There are community centres that could be utilized … for people to find a safe place. People live behind my building … We need housing and we need to put it where they live. Don’t send them to Orleans or Kanata, where they’re going to be detoxing in the suburbs,” she says. “These people are still people. They need a safe place, they need a home.”

Christine Leadman, executive director of the Bank Street BIA, says businesses in the area have been closing as a result of the issues and that “this is an alarm I’ve been ringing since 2015.”

During the pandemic, Leadman says the BIA provided portable restrooms to people experiencing homelessness in the area and distributed naloxone kits to help stop overdoses. In the years since, she says she’s made presentations to city council, worked with police, and started initiatives and roundtables in the community. But the pandemic “escalated the issue to all-new levels” and her authority is limited, she says.

“There’s very little that we can do as far as changing big things that happen on the street,” she says. “This is a problem that’s been ignored, it’s an epidemic that’s been brushed aside, and I don’t see anything from any level that is really looking at how to address this problem.

“The Band-Aid approach is not going to cut it. It needs a fulsome strategy that deals with where it stems from,” Leadman explains. “This is everyone’s problem. It’s every councillor’s problem, and it’s the mayor’s problem”

Leadman sits on the Downtown Revitalization Task Force, and she said the entire city is responsible for solving these issues.

“You want to revitalize the city, you want to revitalize downtown, this is where we start,” she said. “I want to talk about the problems that we know we have that we just need to invest in. We have to stay consistent and we have to stay loud.”

One of the largest issues is a lack of funding for housing, mental health and addiction resources, Leadman adds.

Cotie would like to see Wicked Wanda’s grow in the future and has high hopes for creating a community around intimate wellness in Ottawa, but she “feels really sad” with the current Bank Street situation.

Cotie’s daughter, a certified sex educator, has joined the business and Cotie wants to explore revamping the iconic Barrymore’s building to create a welcoming, sex-positive community and “change the face of an adult store.”

But the people of Ottawa need help, she says. She’s not shying away, she adds, and the city can’t either.

“I have hope for Bank Street. But unless the city does something really, really helpful, businesses are struggling, people are struggling and I’m struggling to make sense of it,” she says. “Our store is really well-loved by the community. That’s what’s kept me downtown, is the people, and the lack of them is pushing me out.”

Cotie has seen people she loved struggle with addiction and mental health and she is no stranger to trauma.

“There’s always lots of healing to do, so I get these people,” she says. “I understand the only difference between me and them is that I’m not addicted. I’ve had my own trauma and most of us have.

“I could make a heck of a lot more money doing what I used to, but I do this because it matters to me from a personal standpoint. The difference between them and me is just one day, one moment, and it changed everything.”