Normally, Ottawa-based labour and employment lawyer Paul Champ is all for a good protest.

He’s been on the board of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association for longer than a decade. He’s testified about the right to protest before Parliamentary committees, been consulted by the UN on the subject and given talks to lawyers in other parts of the world.

“I know that area very well,” said Champ, principal lawyer of Champ & Associates.

(Sponsored)

How shared goals at Tamarack Ottawa Race Weekend strengthen workplace culture

Across workplaces of all sizes and sectors, organizations are continuing to look for meaningful ways to bring people together. Team connection, employee well-being, and community impact are no longer separate

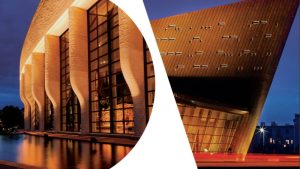

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

Shoe, meet the other foot. The 50-year-old litigator and his small but mighty firm are fighting the Freedom Convoy that’s occupied Ottawa with its big rigs since late January.

“I was very conflicted on taking on that case,” he acknowledged. “I’m usually on the other side. I’m usually supporting protesters.”

Champ has launched a class-action lawsuit on behalf of thousands of residents, seeking $306 million in damages on behalf of his plaintiffs for the disruption to their lives and livelihoods by the drawn-out demonstration.

As well, he persuaded the courts to successfully silence the truckers’ honking horns through a series of temporary injunctions. The loud and persistent noise took it too far, in his opinion.

‘Not what protesting is about’

“It just became more and more disturbing and dark and menacing as the week went along,” said Champ, who heard for himself the extent of the horn blasts. “I couldn’t believe it. It was deafening. To know that that was going on from early in the morning until late at night was unbelievable.”

The demonstrators were terrorizing the public, he said, to pressure the government to drop its public health measures against COVID-19.

“That’s not what protesting is about,” Champ said. “Protesting is about persuading government, for sure. It’s about attracting attention to your issue. In some cases it’s about civil disobedience, but it’s not about inflicting harm on other people.”

Champ is no stranger to the spotlight. As a lawyer who’s seasoned in human rights and constitutional law, he’s handled numerous high-profile cases in his 22-year legal career. He has a strong commitment to doing pro bono work. It makes up 20 to 25 per cent of his practice.

“Access to justice is one of the foundational values in our firm,” said Champ.

“If I was focusing exclusively on paying cases, could I make 20 per cent more a year? Sure, obviously. But would I be 20 per cent happier? No. Quite the opposite, actually. I’d probably be 20 per cent less happy.”

“If I was focusing exclusively on paying cases, could I make 20 per cent more a year? Sure, obviously. But would I be 20 per cent happier? No. Quite the opposite, actually. I’d probably be 20 per cent less happy.”

Paul Champ – principal lawyer of Champ & Associates

Champ has represented detainees in foreign countries, from prisoners held in the custody of the Canadian military in Afghanistan to the long-running case of Abousfian Abdelrazik. He’s the Sudanese-Canadian dual citizen who, while visiting his ailing mother back home during the post-9/11 era, was detained and tortured as a suspected terrorist. It took years for Abdelrazik to clear his name, return to Canada and reunite with his children.

“I’ve always been very interested in the exercise of state power and the way it can be very arbitrary sometimes,” said Champ, who views the law and the courts as one way of making sure governments adhere to basic principles.

The Regina native first studied journalism at Carleton University before earning his law degree at the University of British Columbia. He put himself through school through a variety of jobs. He worked at a group home for children with autism. He went underground as a uranium miner in northern Saskatchewan. He helped mentally ill people from Vancouver’s poor Downtown Eastside by connecting them with social services after they ended up in the courts.

Champ was pursuing his master’s degree in law at McGill University when he started applying to law firms. He said he was attracted to labour law and employment law because they’re areas that deal with the imbalance of power. The law can provide some disadvantaged people “with the ability to, in some way, tip the scales a bit more in their favour.”

Champ was “very fortunate” to have landed at RavenLaw in Ottawa. He said he learned from senior partner Andrew Raven how to persuade the courts in a professional way. It comes down to presenting the facts in a neutral manner, without exaggeration, he discovered.

“You don’t overstate the facts.”

Pushing boundaries

It was important to his reputation as a reliable advocate, he knew, that the courts trust him, particularly when he was arguing a case that could be precedent-setting and pushing the boundaries of the law.

“You have to really lay your groundwork, you have to tell a compelling story, and you have to have the trust of the court that you’re not taking them out on a limb; you’re just taking them a little step further from where the law has been before.”

Champ said he learned a tremendous amount at RavenLaw, working nearly every day during his first few years there before making partner. By 2009, he was ready to branch out on his own, hiring two young lawyers right out of the gate. He has intentionally kept his firm small in order to remain nimble, keep overhead costs down and, most importantly, focus on his cases rather than having to manage people.

The married father of three is often hired by executives to represent them in employment disputes.

“I like to see myself as a problem-solver. If it’s someone who’s already out the door, it’s about getting them a fair amount. If they’re still in the workplace or if they’re someone with a disability, it’s about finding the right accommodation solution for the employer and for them.”

At the same time, what he “really can’t stand” is when a client has a solid case, “but the other side is being stubborn and is not being fair.”

Said Champ: “I’m not afraid to litigate cases.”

One of his precedent-setting wins involved a cross-border employment case that got upheld by the Ontario Court of Appeal.

Champ is also general counsel of Canada’s first union for professional soccer players. On the subject of sports, the lawyer said his biggest challenge when it comes to work is his highly competitive streak.

“The losses burn,” he said with a chuckle. “No lawyer bats .1000, for sure. For the most part, I’ve been pretty lucky.”