Canadians are counting down to the legalization of recreational marijuana this summer, but industry players are already racing to get ahead in a potentially more lucrative market segment for the plant in the years to come: cannabis-based pharmaceuticals.

Companies are researching and developing marijuana-based medicines that, they hope, will not only have broader appeal to doctors and patients, but will create lucrative intellectual property that will provide revenues far into the future.

This is the next level of the “green rush,” said Har Grover, the chief executive officer of Toronto-based Scientus Pharma, a biopharmaceutical company focused on cannabis.

(Sponsored)

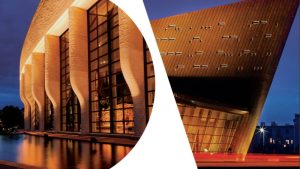

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

How shared goals at Tamarack Ottawa Race Weekend strengthen workplace culture

Across workplaces of all sizes and sectors, organizations are continuing to look for meaningful ways to bring people together. Team connection, employee well-being, and community impact are no longer separate

“The potential down the road is far greater than what the recreational market sizes are… What you need to do is deliver medicine in a form that patients and physicians are used to using,” said Grover.

Ottawa-area firm Canopy Growth, Canada’s biggest licensed marijuana producer, launched its own biopharmaceutical company called Canopy Health Innovations two years ago.

Bruce Linton, Canopy’s chief executive, said its subsidiary has been “running hard” and just last quarter filed 27 patents for combinations of cannabinoids and delivery mechanisms for sleep.

Marijuana companies are eyeing the higher margins these value-added products can command compared to dried bud. Licensed medical marijuana producers also see the associated intellectual property as key to their future profitability, providing a competitive edge and a resilient profit stream as cannabis moves towards commoditization like every agricultural crop.

Smiths Falls-based Canopy and other Canadian licensed producers have been exporting cannabis to countries such as Germany as they open up their medical marijuana markets and require supply.

As Linton expects most of these countries to eventually develop their own cannabis industries, Canopy’s proprietary products and methods can be still be sold or licensed there, generating revenue for the long term, he said.

“Your real advantage is your methods and intellectual property, as well as your unique proven products,” he said.

Canopy and Scientus Pharma are among the 32 firms with a dealers’ license from Health Canada, which gives them more latitude than a licensed producer to conduct activities with cannabis, such as testing. That number is up from just 22 in February last year.

While cannabis itself cannot be patented, licensed producers can apply for plant breeders rights protections for marijuana strains if they can sufficiently prove it is new. But innovations such as formulations, delivery mechanisms, and scientific techniques for testing have the potential to qualify for intellectual property protection.

“There is certainly a desire by companies to develop cannabis products that can have defensibility from a business standpoint, from an IP standpoint,” said Neil Closner, chief executive of licensed producer MedReleaf.

Scientus Pharma and MedReleaf are just two of a slew of Canadian of companies researching and conducting clinical trials examining medical applications for cannabinoids, which are a family of chemical compounds found in the cannabis plant.

MedReleaf has been looking at the efficacy of cannabis for a range of conditions, including cancer and post-traumatic stress disorder. Scientus Pharma has been researching various conditions as well, but is focused on pain management, particularly neuropathic pain for cancer patients.

There is relatively little scientific research into the therapeutic effects of cannabis, in large part due to its long-held illegal status, and there is still much to learn about the plant, said Grover.

“The cannabinoid plant is a gold mine of drug discovery and development for the next 10, 20, 50 years,” he said. “Much like stem cells were 30 years ago, and we’re getting to that stage now.”

And Canada’s relatively progressive cannabis policy gives domestic scientists studying the plant a competitive edge on the global stage.

In the U.S., marijuana use is legal in several states but remains illegal on a federal level, creating legal obstacles for research in the U.S., said Dr. Wilson Compton, Deputy Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse in the U.S.

“If you work in a system that has any federal source of support (funding), there may be concerns… It’s really a conundrum, and that impedes science in some important ways,” he told a conference in Hamilton, Ont., last month.

Meanwhile, the federal government said last week in its budget that it won’t apply a new excise tax to cannabis-based pharmaceutical products that can be obtained with a prescription. That would put it on par with other drugs, such as opioids, which do not get taxed while medical cannabis in its dried form will be subject to the excise tax.

However, to qualify, the cannabis-based product must have a drug-identification number – a classification number from the government obtained after going through a stringent, approval process which allows manufacturers to market and sell the drug in Canada.

Medical marijuana itself does not have a drug identification number (DIN), which has been a deterrent for doctors asked to prescribe it and a barrier for insurance coverage.

Obtaining a DIN typically involves rigorous clinical research, generally including 10-year double blind studies.

The clinical research being conducted by cannabis companies could also get them closer to getting a DIN.

“Having a DIN would be a complete game changer,” said Vahan Ajamian, an analyst with Beacon Securities. “You’ll have no tax on medical, you’ll probably have better insurance coverage… and you’ll get doctors that will see this as real medicine.”