One of the true titans of Ottawa’s “golden generation” of high-tech leaders, Michael Potter took a small consulting company named Quasar Systems, renamed it Cognos and built it into the city’s preeminent software firm in the 1980s and ’90s.

Mr. Potter and his team were trailblazers, helping to transform the business of making software from custom applications created to serve the needs of individual clients to products designed to be used on a wide range of systems around the world.

Under his watch, Cognos became a billion-dollar enterprise. Its signature products – PowerHouse and PowerPlay – became indispensable tools for clients in more than 100 countries, and by the time Mr. Potter stepped down as CEO in 1995 the firm was a world leader in the business intelligence software space.

(Sponsored)

From Davos to WGS: The new mindset of global capital, and what it means for Ottawa

Dr. Anirudh “AK” Kumar sits in CarMa’s headquarters at the ByWard Market, still visibly energized despite having landed from Dubai less than 24 hours ago. The founder and CEO of

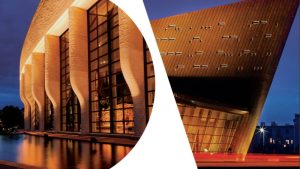

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

One of Ottawa’s true tech trailblazers, Mr. Potter is this year’s recipient of the OBJ-Ottawa Chamber of Commerce Lifetime Achievement Award.

He’ll be honoured Thursday evening at the Best Ottawa Business (BOBs) awards.

Born in London in 1944, Mr. Potter moved to Canada with his family at the age of seven. After graduating from high school in Victoria, he attained his bachelor’s degree in physics from Royal Military College before earning his master’s degree from the University of British Columbia. Following stints in the navy and the federal government, he joined Quasar Systems in 1972, launching a brilliant 23-year at a company that eventually came to be defined by his leadership.

Now 72, Mr. Potter recently sat down with OBJ to talk about his business career and his many other passions. What follows is an edited transcript of that conversation.

OBJ: During your three years in the navy, you already knew you wanted a career outside the military. How did you prepare for that?

MP: Having in mind that I wanted a civilian career, I actually did a little bit of lobbying to suggest that rather than send me to sea – three years that would be a lot of fun but wouldn’t lead anywhere for either me or them – I felt I would be more useful working at a desk job using the full education that I had, and they agreed. I joined the Defence Research Board, a half-civilian, half-military research organization that provided analytic services to the military.

OBJ: That obviously provided a pretty good foundation for what came later.

MP: It did. I was working in a field called operations research, which used applied mathematics, mainly computer-driven, to analyze supply chains or queues or to help design and optimize manufacturing processes. I hadn’t studied that in university, but I had the mathematics skills to figure out the kinds of problems we were dealing with. After three years I came out of uniform and did the same kind of work for the federal government for an additional year.

OBJ: You joined Quasar Systems (the forerunner of Cognos) in 1972. Within three years, you owned the company. How did that come about?

MP: Quasar provided services to create custom-built software under contract, initially almost entirely to the federal government. Although there was a good living to be made in that business, expansion geographically beyond Ottawa was difficult, and secondly, being service-based there was no leverage to it.

I was young and had no family to worry about, so perhaps I was more of a risk-taker. I told the partners it would be worth their while and mine if I acquired the company and took it beyond custom software services.

OBJ: Early on, you brought in a guy you’d worked with previously, Bob Minns, who ended up playing a huge role in the growth of what became known as Cognos. Can you talk about your relationship?

MP: Bob was an extraordinarily important guy to the whole Cognos story – he’s not as well-known as he should be. I worked with him on a project in the federal government. When I moved to Quasar, I asked him to join me.

Once with Quasar, Bob had the bright idea, which was quite revolutionary at the time, that you could develop a higher-level language which could allow an end user, not an IT specialist, to be more directly involved in actually writing code that would extract data and write the summary reports that he needed.

That higher-level language was independent of any particular application, so it could be standardized and packaged as a product. Bob then developed the idea and we released our first software product in the early ’80s. The margin for selling these products was much higher. The geographic constraints of having our people at each customer site were gone, so we could sell it internationally. It just took off. The product was a roaring success commercially.

OBJ: That product, called Quiz, spearheaded the firm’s transition from a service-based business to a product-based business. What were some of the challenges involved in that transition?

MP: In our services business, very little attention, if any, was paid to marketing, sales, distribution and after-market support. All of that was new to us. The transition was much like going from managing a law firm or an accounting firm to running a manufacturing business. We weren’t manufacturing anything tangible – it was software – but we still needed the various functions of research and development, product packaging, marketing, sales and distribution, after-market support.

The business model for that was the manufacturing business. This is well understood in the software industry now, but it wasn’t in the early ’80s. That was a big change for us, and it required people from outside the software services business. For example, someone like (former vice-president) Robin McNeill didn’t come into the company with any software experience – he was a communicator.

He thought always in terms of what problem are you solving; how do you create a message which will convey quickly to a potential customer that you understand his problem and we have a product that will solve it? Another example: Alan Rottenberg (who became senior vice-president of marketing and business strategies) was a specialist in marketing and distribution.

Over a small number of years, the original team of people who were in the custom software business – programmers and systems analysts with some limited management and marketing capabilities – was augmented with marketing people, salespeople, service and customer support specialists. There were still programmers in the R&D group, but elsewhere in the company a much broader range of skill sets was needed.

The organizational transition needed to be very rapid because the product was so successful and also because we recognized that, even when the product-based business was in its embryonic form, it was clearly where the growth and the profitability would come from, so that’s what we invested in.

The challenge was to take what appeared to be a diversified business and say, no, we’ve got to focus on what is really going to grow. If we hang on to the legacy (service) business, it would hold us back. It’s almost faded from everyone’s memory now, but at the time it demanded a lot from everyone.

OBJ: Your next product, PowerHouse, was fittingly named because it turned you into a powerhouse.

MP: PowerHouse was an extension of the original Quiz reporting product with much broader functionality. It was aggressively marketed internationally – in the U.S., Europe and farther afield in Australia, New Zealand and Asia – and Powerhouse became a $100-million business. It was a very exportable product and we had a great team behind it. We went public in ’86 on the strength of the growth of that product.

OBJ: And then you transitioned into desktop business intelligence software products, which led to PowerPlay.

MP: Yes. The platform for the earlier PowerHouse product was the mini-computer, which gave users access to centralized data through terminals. When we developed PowerHouse, there were no personal computers on people’s desks and no graphical user interfaces. We realized as we got into the latter part of the ’80s that Microsoft’s graphic user interface and decentralized computing were going to change everything for us.

There was a lot of discussion in the company how PowerHouse could migrate into that world. It turned out the most effective approach was to invest significant R&D resources to create a new set of products to address desktop computing and graphical interface. That’s where the business intelligence idea – PowerPlay – came in.

Initially the development was a joint project with an existing PowerHouse user – Procter & Gamble. They were interested in developing analytical tools to look at marketing and sales of their different brands. They trusted our technical capabilities because they were strong users of PowerHouse. Under our agreement with P&G, they would be the early adopter of a new analytical product we would develop, giving them a competitive advantage. But contractually, the intellectual property rested entirely with us.

So it was a terrific way for us to do some innovative new product development alongside end users who could tell us exactly what they wanted in that product and, at the same time, have much of our R&D funding provided. And by the time we directed PowerPlay at the broader market, we had a large successful user and a great reference. It all turned out to be terrifically successful.

OBJ: Eventually, business intelligence software became your bread and butter.

MP: It’s what became the bulk of the business. But, again, there was a challenging transition not unlike the shift from software services to software products. Our employees and our organization had a great deal of investment and expertise in an older technology base – and older platform. And existing PowerHouse users did not want to be treated like a “legacy business.”

There was lots of talk internally about whether the two products (PowerHouse and PowerPlay) could be put together. Many people in Cognos favoured that approach, and significant R&D resources were spent trying to integrate the two and bring PowerHouse on to the new platform. But ultimately, it really was a new business intelligence product that became the business that eventually reached $1 billion revenue and attracted the attention of IBM (which bought Cognos for nearly $5 billion in 2008).

There was still some legacy business for PowerHouse, but predominantly it was a transition that once again migrated an entire company over to a new product.

OBJ: After 23 years at the company, you decided to step down as CEO in 1995. Why did you decide to leave at that time?

MP: I was over 50 at the time and obviously the company had done very, very well. Being the CEO of a growing company is absolutely a full commitment – long hours and lots of travel. Some people – and I admire them for it – manage to find a balance between family life and business life. For some of us – and I was one – it was harder to find that balance. And like any company, as it grows, it benefits from a different style of management and from executives who are accustomed to and interested in managing larger organizations.

OBJ: Have you ever had any regrets about leaving when you did?

MP: Not at all. I recall that, following the announcement of my resignation, I was asked by a journalist: “Mike, why would you step down now when things are going so well?” I think I replied something like: “What’s the alternative? Is it better to step down when things are not going well?” It was a good time for me to leave. New management would take over an organization in good shape. The challenges were all positive ones – like growth and how to manage it.

And looking back on it, I realized that I didn’t want to define myself as a businessman. Business was a means to an end. Yes, I was fascinated with the challenge of managing people and building a business. I learned an awful lot doing it, but I wanted to explore some of my other interests – flying, sailing – to travel without just going in and out of a glass office tower, and to read things that were not about business management and technology.

I also didn’t think I was too old to think about kids and a family. I felt I would rather be known for some of those things than just being a successful businessperson. Stepping down as CEO at age 51 wasn’t a hard decision for me.

OBJ: Speaking of flying, you used to pilot your own aircraft to business meetings. How did that passion for flying emerge?

MP: I’ve been flying since I left university. Initially I was flying gliders strictly for fun. Then I started to use light airplanes to travel for business. I had enough flying experience to get from A to B fairly reliably, and over many years acquired more capable airplanes and added to my own flying skills – an instrument rating and then an airline transport rating – and I ultimately flew turboprop aircraft and business jets.

When I had the opportunity after Cognos, I went back to my roots of flying for pleasure. I’ve have also had a passion for older aircraft, and I, somewhat impetuously, bought a Second World War Spitfire in 2000. It wasn’t a reproduction – it was the real thing. I learned to fly it, which was sort of a challenge, and I rather enjoyed the interest that many Canadians have in those old historic airplanes.

I decided to acquire a collection of these classics and also took the steps required to create a charitable foundation called Vintage Wings of Canada with a mission to show the Canadian public, and particularly young people, what the history of aviation represented. We felt that people wanted to see these old warbirds as they were designed to be flown.

We’ve displayed the collection at an air show here in the Ottawa region for a number of years as well as at other shows. I still fly the classics, but I have recently got quite addicted to aerobatic flying and spend more of my time in a modern aircraft designed for that. I don’t know what it is – sometimes I think I might get too old for this – but I just love to explore the full range of an airplane’s capability. It’s an immense amount of fun and a challenge that has no limits.

OBJ: What else occupies your time these days?

MP: I now have three daughters aged 18, 19 and 13 and they are the most important part of my life, as you can imagine. I couldn’t possibly have combined my business life and my family life. It wouldn’t have worked, and I think I would’ve disappointed myself in terms of being a parent.

But when I finished my business career, I felt I was still young enough to be an active father. I suppose I also felt that I’d learned a few things that I might be able to share as they grew up, and I had a degree of financial independence I could use to give them some opportunities, both to travel and to give them a financial base to begin their adult life. I guess it was all a gut feeling, rather than a plan, but it became central to my transition from a businessperson to someone with more diverse interests.

OBJ: How have some of those diverse interests influenced your family life?

MP: I’ve always been interested in being on the water and messing around in boats. We have a family boat, and all the kids and myself are on the water quite a lot. We’ve had it as far east as Istanbul and as far west as New Zealand. Out on the water, it’s just a whole new world, literally. My youngest (daughter) was spearfishing when she was 10. We dove the Galapagos for a week a few years ago. I’ve been delighted to give them that experience; I’m not sure if they realize how big an opportunity it is.

OBJ: Do you still keep tabs on the local tech scene?

MP: I wouldn’t say I have stayed up to date. The industry has moved so fast. I did invest in a few companies shortly after I left Cognos. I was very happy to be (an investor in) Kinaxis – it’s done very well – and several others. Most recently, I’ve come to know (Shopify’s chief operating officer) Harley Finkelstein. He has a lot of interest in the history of the software business and we’ve talked a lot about that. So do I keep an eye on it? Yes, but I’m not involved any longer.

OBJ: What do you think of the new wave of tech enterprises in Ottawa?

MP: I’m delighted. There’s no question there’s huge opportunity in software today – greater by orders of magnitude than when I was in the business. I’m delighted to see that some Ottawa-based firms are getting a very significant piece of that.

It would be for others to judge, but I suspect there’s perhaps some truth to the idea that some of the expertise that was built up in Ottawa during our time – not just at Cognos, but by a number of companies in the ’80s and ’90s – provided some kind of base for the expertise that is now drawn upon by firms like Shopify. I think it’s wonderful.

OBJ: What accomplishment are you most proud of?

MP: Well, raising my kids has been my most important job, and I think they are terrific. In my business life, I could not be happier in the journey a lot of us took with Cognos and the way it has turned out. But I can’t take credit for that.

All my experience has shown that it wasn’t top-down decisions or boardroom strategy that gave rise to the great ideas at Cognos. Those ideas very much bubbled up from lower levels in the organization, and very early on, I came to understand that the most important role I had as a CEO was to motivate people, make them feel that they had the freedom to explore different ideas, to support what they were doing and to stay out of their way.

I also credit the whole organization, not just me, with Cognos having the unusual ability to undergo some really major transitions without missing a beat. They were not easy. People invested their careers in becoming very good at something and they then had to be willing to perhaps walk away from a lot of that expertise and take on something new if they wanted to be part of that transition. It became part of the culture of Cognos.

It’s very, very hard for companies to transition from one technology base to another. Cognos did it twice. I’m really proud of the people who were able to pull that off.

OBJ: If you could offer any friendly advice to the new generation of tech leaders, what would it be?

MP: I would say that the most important quality that served us well was perseverance. It’s easy to perhaps look back on Cognos’s history and see just a constant, steady rise to the point it is today. But it was a little more bumpy than it might appear. For any fast-growing organizations, there are going to be some real obstacles that are placed in your way and there are going to be a lot of things that don’t go well; there will be a lot of opportunity to say, “I give up” or “Is it worth pursuing?” No one can succeed if they are not willing to fight past those difficult times.