After meeting with executives from local venture capital firm Wesley Clover last week, I left with a feeling that I’d just experienced a Bizarro moment.

For those of you who have never heard of Bizarro, he’s a character related to the Superman comic series – circa 1958 – who did everything backwards. And after my meeting with Wesley Clover’s Andrew Fisher and Greg Vanclief, together with my Telfer School of Management colleagues Barb Orser, Tyler Chamberlin, Mark Freel and Alain Doucet, I had the feeling things were similarly reversed at Wesley Clover.

Unlike most VCs, WC first sources ideas from its more than three million enterprise clients and suppliers. Then the firm recruits top student entrepreneurs to form engineering and business teams, to both solve and commercialize those real-world problems.

(Sponsored)

Borden Ladner Gervais LLP and partners lead with generosity

Borden Ladner Gervais LLP (BLG) are no strangers to supporting charities in the nation’s capital. From the Boys & Girls Club of Ottawa to Crohn’s and Colitis Canada to the

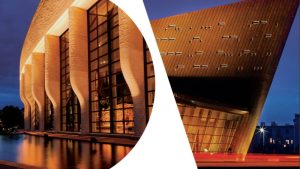

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

According to Mr. Fisher, no VCs anywhere do this – except maybe for Cisco’s internal incubator.

So instead of waiting for proposals and ideas to come to them from outside their huge watershed (which includes clients, customers and suppliers of March Networks, Mitel, DragonWave, Bridgewater Systems and many other companies in their diverse portfolio, plus strategic partners such as Telus, SaskTel and Vodafone), they generate them internally.

That way, they avoid hearing from entrepreneurs with cockamamie ideas like you so often see on CBC’s Dragons’ Den, say. Also, they stay on-point – the focus of these ideas are within their areas of expertise.

It’s a formula that seems to be working, as WC has a pretty good track record: Before Newbridge – another (former) member of the Wesley Clover watershed – was sold to Alcatel-Lucent, it spawned 35 independent companies, of which 34 were successful. That’s a phenomenal success rate. These spinoffs returned $900 million to Newbridge’s treasury alone, plus more to the entrepreneurs responsible for them.

So the model works.

What WC is looking for are top engineering and business students straight out of university or college who want to be “intrapreneurs” – people who work within their system in teams and have the same skill set as entrepreneurs, but don’t necessarily like the risk profile of going it alone.

The philosophy of the whole cluster comes directly from the chairman, Sir Terence Matthews. Terry insists that every startup follows the same set of 10 principles:

1. Early attachment to the customer;

2. Follow the fastest (least effort) route to revenue;

3. Be consistent with enterprise goals;

4. Team-focused – superstars park your egos at the door;

5. Follow your mentor’s advice;

6. Create a great business first and cool technology second;

7. Keep your costs down;

8. Leverage the investment with government grants and other people’s money;

9. Follow a global mandate – Canada is too small to be the primary focus;

10. Go after every geography and every vertical.

When a team proudly reports to the chairman that they met their quarterly sales goals, Terry often berates them for not having doubled or trebled it. They tend to leave quite chastened.

The results, however, speak for themselves. WC’s track record over the last 30 years is that for every $1 invested, they have returned $13. Student entrepreneurs get paid a wage to work in the system and decide themselves how much of their pay package they want to invest in the shares of their own startup – keeping in mind that $1 less they take home today could be worth $13 some day.

What WC looks for in student entrepreneurs includes:

a) A strong work ethic;

b) If they came from a large family and had to scrap for things;

c) How much their parents did for them at a young age;

d) How good their communications skills are;

e) If they have some humility about them and can they learn;

f) If they can network with everyone;

g) If they can create positive outcomes from each meeting;

h) If they can sell.

Every person who enters the WC system must spend six months cold-calling and generating leads. Are they tough enough to last? Along with this, every core team member is interviewed by Sir Terry. Can they survive his scrutiny?

WC is focused on telecom and wireless but they are also interested in some new areas such as digital media, animation, film – it is helping produce four horror films for Brookstreet Pictures, a company fronted by Terry’s son Trevor Matthews – mobile apps, network-based real-time content and software.

Right now WC has six startups here in Ottawa, with a new office to be opened soon in China. It says it would like to have a closer relationship with Ottawa-area universities and colleges, and wants more top local students referred into its programs.

But it also wants some indication from the academic community that it can help equip the next generation of entrepreneurs with the skill sets they need to lead global-spanning enterprises. These skills include strategic selling and business communications, areas the Ontario education system tends to overlook.

Bruce M. Firestone, entrepreneur-in-residence at the Telfer School of Management at the University of Ottawa, is founder of the Ottawa Senators and executive director of Exploriem.org.