Does Ottawa really need a highway cutting through the middle of the downtown core? That’s the question local architect Martin Tite often asks himself about the Queensway.

Already an Insider? Log in

Get Instant Access to This Article

Become an Ottawa Business Journal Insider and get immediate access to all of our Insider-only content and much more.

- Critical Ottawa business news and analysis updated daily.

- Immediate access to all Insider-only content on our website.

- 4 issues per year of the Ottawa Business Journal magazine.

- Special bonus issues like the Ottawa Book of Lists.

- Discounted registration for OBJ’s in-person events.

Does Ottawa really need a highway cutting through the middle of the downtown core? That’s the question local architect Martin Tite often asks himself about the Queensway.

“It just came out of observation and seeing this thing and thinking, gosh, that’s an awful lot of investment in this thing,” he told OBJ Tuesday. “You’re driving by some of these intersections and realizing (the highway) actually occupies acres of land. And that land is very valuable, especially around the core.”

The Queensway is a segment of Highway 417 running east-west through the city from Carling Avenue in the west to Nicholas Street near the University of Ottawa. For most Ottawans, it’s the most obvious way to get in and out of the downtown core.

But, it also takes up a significant amount of land — 160 acres, according to Tite.

“Get your head around this: that’s equivalent to 50 blocks of downtown Ottawa,” he said.

So Tite wondered if the land currently taken up by the highway, which was constructed in the 1960s, could be reimagined for other uses in addition to transportation.

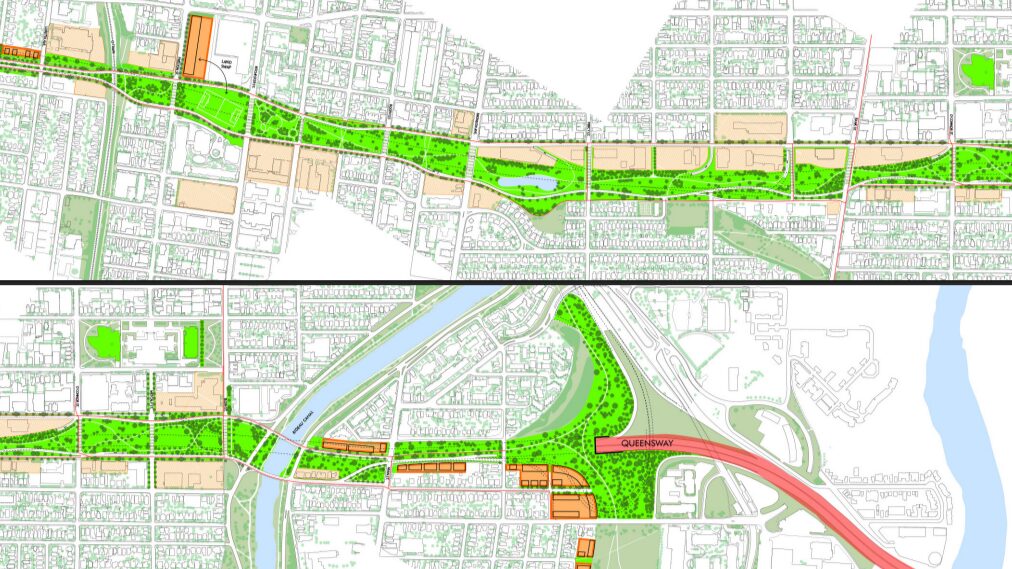

Alongside colleagues at his firm, Montreal-based Provencher_Roy, Tite undertook an informal study of the highway to evaluate how it could be transformed to introduce more greenspace and open up new land.

“If we rethought the thing completely, we could actually make that area along the downtown area one of the most desirable places to be in Ottawa,” he said. “That comes along with increased property values and lots and lots of opportunities for redevelopment. That land is right now being dedicated entirely to the roadway and embankments.”

The firm's case study raised three possible options, varying in cost and complexity.

At one end of the spectrum are changes that could be made in the short-term, which Tite said would address concerns about nearby property values. Changes would include investments in the highway’s appearance and surrounding landscape, including removing more “hostile” elements such as chainlink fences where not needed. Those kinds of changes, he said, would improve the character and quality of the space.

If the city were really ambitious, Tite said the most radical proposal would be to move the highway underground.

In between those two options is another possibility: turn the high-speed, multi-lane highway into a boulevard or parkway, surrounded by urban greenery.

“The land becomes very, very high value,” he said. “It would encourage redevelopment and intensification of use in the vicinity. What we have right now is 85 acres of brownfield and 75 acres of asphalt. When we remove the Queensway, all of a sudden all of this territory becomes available to us.”

Such a project, he said, would create 92 acres of new greenspace, equivalent to LeBreton Flats or twice the size of Lansdowne Park.

He said it would also create 22 acres of property fit for development, while also revitalizing underdeveloped land currently neighbouring the Queensway. That land could be used for anything, he said, from public buildings such as hospitals and schools, to community amenities including recreational centres, parks and libraries. It could also host shopping centres, offices, utility facilities and housing.

“The housing one is really, really obvious to me,” he said. “Housing and finding properties that are close to transit, there’s not a lot of them right now. And finding land, there’s not a lot that doesn't involve going out and tearing up farmland.”

To offset traffic concerns, Tite suggested that transit could be developed alongside the highway, the LRT could be expanded, or a subway corridor or streetcar line could be introduced.

But why transform the Queensway at all?

Other than Tite’s complaints that the highway is an eyesore and waste of land, he said its placement near the core means it divides and degrades nearby neighbourhoods, while also reducing property values.

The current infrastructure isn’t working well, he added, leaving commuters in standstill traffic at all hours of the day. Plus, he said money will need to be invested into the highway every year for maintenance.

But a bigger issue, he said, is that transportation won’t look the way it does now in 50 years.

“I don’t think we’re going to be driving cars the way we do now,” he said. “So let’s look ahead. Let’s imagine the possibility of a different kind of infrastructure. One of the problems we have is that there’s a colossal amount of inertia behind the way things are done now. We’re stuck in this mode of simply repeating what we’ve done before.”

When it comes to major highway redevelopments, there is precedent, he said. Cities such as Seattle and Dallas in the U.S., Hamburg in Germany and Seoul in South Korea have all reimagined major roadways as public spaces, parks and housing.

Boston’s “big dig” project is one significant example.

“They essentially rerouted the whole series of freeways that ran through historic parts of the city in the ‘50s and ‘60s, which really had a bad effect on the city,” said Tite. “They said, ‘This can’t go on. Let’s bury this stuff.’ And they did. In the process of doing that, they improved the quality of the entire city as a whole and now there’s a colossal linear park running through the middle of Boston.”

According to Tite, his informal study only scratches the surface of what could be done with the Queensway. Next steps would be securing seed money to further craft and test a business case, he said.

“It would be very interesting to see if this thing has legs,” he said. “We haven’t really tested it in that way at all. Maybe there’s something here and it’s worth trying to find out.”

While such an ambitious and expensive project would almost certainly get pushback, Tite said projects like Lansdowne and LeBreton Flats have shown that people are more open to big ideas that might have seemed impossible before.

“The city’s changed an awful lot in the last few years,” he said. “But are people ready for this? I don’t know. The light-rail project famously had problems and I would imagine that’s going to make people gun-shy. But I think we need to think bigger. This is the national capital of a G7 country. Let’s act like it.”