For public relations executive Terance Brouse, the office is where creativity flows.

On Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, employees at Maverick PR work from the firm’s office — a converted red brick Victorian home in Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood.

“We come to the office on the same days because we need a quorum,” said Brouse, the firm’s vice-president of client services. “That’s when the brainstorming and those ‘aha’ moments happen.”

(Sponsored)

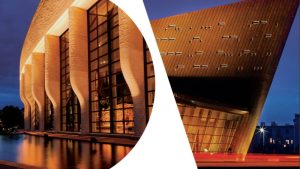

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

How shared goals at Tamarack Ottawa Race Weekend strengthen workplace culture

Across workplaces of all sizes and sectors, organizations are continuing to look for meaningful ways to bring people together. Team connection, employee well-being, and community impact are no longer separate

On Thursdays and Fridays, employees work from home on different tasks. “It’s when we put our heads down to focus on writing and getting work done,” he said.

Many companies are transitioning to hybrid work schedules from the work-from-home policies that developed by necessity in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet how to strike a balance between office life and remote work remains an enduring challenge for many businesses nearly three years after lockdowns upended how many Canadians work — one that’s made more difficult by the differing expectations between employers and employees.

Some organizations offer workers the freedom to choose which days they go into the office.

Others have a set number of office days, with attendance varying from informal guidelines to rigid mandates.

“Everyone is trying to find that happy medium or that hybrid work sweet spot to make this really work,” said Maria Pallas, director of strategy and optimization for Lauft, a network of on-demand workspaces.

“But everyone’s not always on the same page.”

Indeed, new research has uncovered a disconnect between employee work preferences and the expectations of employers.

A survey by Cisco Canada released Thursday suggests that while employees increasingly expect flexibility, employers continue to see hybrid work arrangements as a perk.

The poll, conducted by Angus Reid in December, found that 81 per cent of Canadian workers want a flexible work arrangement — and are willing to leave their current job to get it.

In fact, flexibility emerged as a top priority among workers polled, second only to salary.

But the survey found that the majority of employers were tightening hybrid work policies and ushering in mandatory office days.

The research illustrates a gap between employee and employer expectations as work is redefined in the post-pandemic era.

“At the highest level, there’s satisfaction overall with hybrid work amongst both employees and employers,” said Shannon Leininger, president of Cisco Canada.

“But when we dig into the numbers, there’s a tension between the expectations of employees and employers,” she said. “Employers feel like hybrid work is a benefit. Employees feel like it’s expected.”

Workers seem to be resisting the transition back to offices for two main reasons: time and money.

Canadians who work from home save an average of 65 minutes a day normally spent commuting, research published last month by the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research found.

For workers in bigger cities, remote work can sometimes shave as much as three hours off a work day — time experts say can instead be spent on health and wellness, time with family and other activities that support a strong work-life balance.

“We know now what it’s like to be able to work a full work day and still be able to drop off kids at school and do a load of laundry,” said Andrea Bartlett, vice-president of people at Humi, a company that offers an integrated HR services platform.

“Once people have experienced that flexibility, it’s hard to take it away.”

The Cisco survey found that women are more likely than men to value flexibility, with 59 per cent of women saying flexibility and choice in how, when and where they work was a top priority, compared with 51 per cent of men.

“What I repeatedly hear from women is this feeling that I no longer have to choose between my family and my career,” Pallas said. “I can do both. I can do well at my job and handle my responsibilities and serve my clients but … I can be home with my family for dinner. I can pick up my kid from soccer practice.”

Meanwhile, workers report saving thousands of dollars a year working from home, saving money on everything from coffee and lunches to parking and transit.

Research by Cisco released last year found that employees saved $11,100 annually on average working in a hybrid model.

To address the rising cost of living, some companies have considered offering workers a commuting stipend as part of a return-to-office mandate, Bartlett said.

“Some people left the city because the cost of housing just skyrocketed. What do you do if you’re mandating workers back to the office but an employee who used to live downtown now lives in Aurora?” she said, referring to a town about an hour north of downtown Toronto.

While a company may have the legal right to determine where an employee works, the shortage of workers has empowered workers to have a greater say over their work arrangements.

“We have a tight labour force market,” Leininger with Cisco said. “There’s a heightened demand for skills … organizations that offer a hybrid model with more flexibility and choice will reap the greatest benefits.”

While one of the downfalls of mandating office days could be losing workers, experts say there are also risks to not having face time with colleagues.

“From an employer’s perspective, there could be concerns about a loss of learning through osmosis if everyone is at home,” Bartlett said. “They might also be concerned that employees are less connected to what the business is trying to do.”

Experts say finding the right hybrid work schedule ultimately comes down to what works best for both an organization and individual workers.

“There’ll be some trial and error,” Pallas said. “We’re figuring things out as we go. We’re still in the dust-settling phase of a very abrupt and rapid change.”

Leininger admits she’s made some missteps.

“We don’t have it all figured out. I’ve certainly made mistakes in my hybrid work model,” she said.

“You need to experiment, course-correct and then try something different.”