Buyers in Canada’s most overheated real estate markets paid an average of $229,000 extra per home between 2007 and 2016 because of regulations making it difficult for builders to construct more single-family houses, said a new study.

Research from the C.D. Howe Institute released Tuesday showed that prices were up by about $112,000 in Ottawa-Gatineau over that ten-year period, below other overheated housing markets such as Toronto and Vancouver.

The study revealed that zoning regulations, development charges and housing limits in and around southern Ontario’s Greenbelt have added around $168,000 to single-family houses in the Greater Toronto Area and about $644,000 to the cost of others in Vancouver – a number the non-profit research organization says draws comparisons with Manhattan and U.K. housing.

(Sponsored)

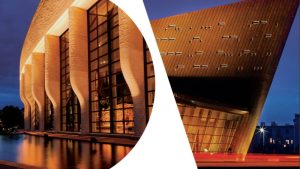

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

SnowBall 2026: A premier networking event with purpose returns to 50 Sussex Dr.

As winter settles in across the capital, one of Ottawa’s most high-profile charitable and business networking events is set to return to its roots: On Wed., March 4, 2026, The

The organization’s study also found regulations caused single-family home prices in Victoria to increase by about $264,000 and by about $152,000 in Calgary.

Benjamin Dachis, C.D. Howe’s associate director of research and a co-author of the study, said development charges levelled by cities to fund the infrastructure needed for new housing are largely responsible for some of the increases.

“Most people can’t afford to pay for their house all up front with cash, so they get a mortgage and pay for a house over time, but that is not what cities are requiring. They are requiring developers to pay for the municipal infrastructure all up front and not over time, so that all gets loaded onto the sticker shock of housing,” he said.

Dachis said his study proves that the charges are “flawed” because they get passed on to buyers. He thinks cities should look to allow them to be paid over the course of a house’s existence, rather than when it is built, to help mitigate skyrocketing prices.

He also said his research found that prices spike when it is difficult for developers to get permits based on intensification and densification targets and when they are contending with restrictions on development on land between urban growth boundaries and the Greenbelt – a 7,200 square-kilometre swath of land that borders the Greater Golden Horseshoe region around Lake Ontario and was protected from urban development by legislation in 2005.

The Greenbelt has become a hot topic in the lead up to the June 7 election after Progressive Conservative leader Doug Ford vowed to allow housing development on the Greenbelt only to backtrack later. His competitors, Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne and NDP Leader Andrea Horwath, both slammed Ford’s initial promise, extolling the need to protect the green space.

The C.D. Howe study found allowing development on land dedicated for the Greenbelt could reduce single-detached home prices by around $50,000 in Hamilton and between $25,000 and $30,000 in York and Halton regions alone.

Modestly increasing land availability for housing while cutting development and zoning costs would have an even larger affect. It would slash the cost of a single-detached house by more than $70,000 in Toronto, Peel and Durham regions, $90,000 in Halton Region, more than $100,000 in Hamilton and around $125,000 in York Region, the study said.

To reach such conclusions, Dachis and co-researcher Vincent Thivierge looked at two things – what financial challenges developers have to deal with and by how much they increase the cost of housing, and what the gap is between the cost of housing for a buyer and what it costs to build that housing.

They found Vancouver and Toronto, which are both experiencing “high” demand for housing, had construction costs around $350 per square foot in 2016.

The cost of development in Edmonton topped any other Canadian cities between 2007 and 2016 because competition for high-paying jobs in the nearby oil sands industry had driven up labour costs.

Abbotsford B.C., Kingston, Ont., and cities in New Brunswick fared much better, landing average construction costs of about $200 per square foot or less in the same time period.

Interested in the National Capital Region’s real estate market? Check out the most recent episode of the Ottawa Real Estate Show below, where Windmill Development’s Jeff Westeinde talks about the transformative potential of new developments coming to the western edge of downtown Ottawa.