It’s an exasperating truth many consumers know all too well: the price you see on the tag or in the ad is very often not the price you get.

For example, I went online looking for tickets for an upcoming Cirque du Soleil show at the Canadian Tire Centre – and found prices ranging from $122 to $280 for similar seats.

Why the price discrepancy? The $122 price was for a ticket purchased from the Canadian Tire Centre. The $280 ticket was from a ticket reseller whose website stated: “We are a resale marketplace, not a box office or venue. Ticket prices may exceed face value. This site is not owned by Canadian Tire Centre.”

(Sponsored)

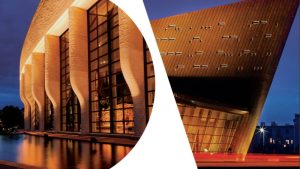

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

Powered by passion, backed by Ontario Made: Turning bold ideas into entrepreneurial success

Back in the winter of 2018, a brutal cold snap dropped temperatures in Merrickville to -46°C. Michael J. Bainbridge and Brigitte Gall looked outside and told their holiday visitors to

The same day, my wife went online to buy a pair of tickets for the Rogers Cup men’s tennis tournament in Montreal this summer. She thought she was purchasing the tickets from the organizers. But it turned out she was buying from a ticket reseller. The fine print on the order confirmation said the ticket seller was “in no way associated with the Rogers Cup.”

Fortunately, in my wife’s case, the reseller’s price markup was only about $10 per ticket. We overpaid by only about $20, plus sales tax, which is almost 15 per cent in Quebec.

For the Cirque du Soleil performance, the Canadian Tire Centre’s price for a ticket in the arena’s 100 level had a face value of $100. That included sales tax but did not include a “ticket fee” of $15.40. Also added to the purchase price was a charge of $3.40 towards refurbishing the arena at some future date (!) and an “order charge” of $3.50. That’s an all-inclusive cost of $122.30 – a hefty markup of more than 22 per cent above the advertised price. And that’s before any delivery charges, such as having the tickets sent by mail, which costs an extra $2.

The reseller’s advertised price for a ticket in the 100 level was $210, including tax. On top of that, there was a “service charge” of $63 and an e-mail delivery charge of $6.95, for a grand total of $279.95.

The lesson I learned here is that I must be more careful when using Google to find websites on the Internet. For example, when I searched Google for “Canadian Tire Centre,” the first website it showed me was for a ticket resale agency. I had been ignorant of the fact that Google gives prominence to those who pay to advertise on its site. And I was unaware that, at a quick glance, advertisers’ websites might lead some people – me included – to think they were buying tickets directly from the event organizer.

Generally speaking, I don’t like shopping on the Internet. I like to see what I’m getting before I buy. But I make an exception for tickets for entertainment and travel.

Buying online or by phone seems to make it more likely that we’ll be stiffed by unscrupulous sellers with add-ons that greatly inflate the advertised price. Is anybody taken in by those TV ads that always say they’ll offer you two for the price of one and just add additional shipping?

The airline industry is another sector notorious for charging total fees far in excess of advertised fares. Airlines such as Air Canada routinely used to add hundreds of dollars to advertised fares to cover the cost of fuel, landing fees and other charges. That is, until the federal government recently introduced rules requiring airlines to switch to all-inclusive prices in their advertising.

Now, for example, Air Canada’s advertising is a model of clarity. And the government’s Canadian Transportation Agency rightly notes that the new rules allow consumers “to more easily compare prices and make informed choices.”

The agency says on its website: “The display of the total price in air price advertising reduces confusion and frustration as to the total price and increases transparency.”

Amen to that. So why can’t – or won’t – more Canadian retailers be upfront with their customers by including taxes and all costs in their advertised prices?

Mattress Mart might offer a clue. In Ottawa, the retailer used to set an example by displaying all-inclusive prices.

Much to many consumers’ chagrin, it no longer does so. I asked a store employee why. He told me: “Our customers would see a mattress advertised for less in a competitor’s store. What the customer didn’t notice was that the competitor’s price was higher than ours once the sales tax was added.”

However, the reluctance of many businesses to be more transparent with their customers can be self-defeating.

For example, I almost never take a train anymore. One reason for this is a lack of transparency in Via Rail’s advertised pricing.

Via recently advertised Ottawa-Montreal fares starting at $27. This was one-way, but the advertisement didn’t say that. The cost of a return ticket from Ottawa to Montreal turned out to be almost $90 with taxes included.

Many other companies are guilty of the same practice. Holland America, a favourite cruise line of mine, advertises prices without including taxes, fees and port expenses, which can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of a weeklong cruise.

But let’s give praise where praise is due. The National Arts Centre’s prices include taxes.

Gasoline retailers are required by law to post all-inclusive prices, but they aren’t required to prominently display these prices where passing motorists can see them. So good on them for doing it anyway.

And good for the Liquor Control Board of Ontario and the Beer Store, both of which include taxes in their prices. I suspect the Ontario government likes it that way, so we don’t know just how much we pay in liquor and beer taxes.

Michael Prentice is OBJ’s columnist on retail and consumer issues. He can be contacted at news@obj.ca.