For more than 20 years, Trina Mather-Simard has been a trailblazer in the Indigenous tourism industry.

Her company, Indigenous Experiences, has led the way in celebrating Indigenous culture within an urban Ottawa setting. It operated its popular tourism destination for 18 years on Victoria Island in the middle of the Ottawa River, becoming the first Indigenous tourism experience to be part of Destination Canada’s Signature Experiences collection. The attraction moved in 2019 to the grounds of the Canadian Museum of History.

Mather-Simard is also behind the success of the Summer Solstice Indigenous Festival, transitioning it during the COVID-19 pandemic to a virtual format. Its audience grew to more than half a million people this year.

(Sponsored)

OCOBIA eyes Ottawa BIA expansion as it gears up for election year

Michelle Groulx says it’s not difficult to spot the Ottawa neighbourhoods with their own business improvement area (BIA). That’s because, she says, BIAs are a visual and experiential representation of

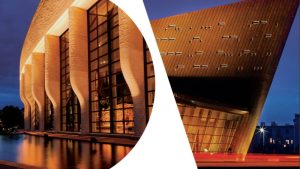

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

Now, she and her team have launched a new agritourism destination called Mādahòkì Farm in the NCC greenbelt, signing a 25-year lease with the National Capital Commission. They took possession of the property at 4420 Hunt Club Rd. on Oct. 1st. It was formerly a special events venue for Lone Star Ranch and Catering.

Mādahòkì Farm is hosting four seasonal festivals throughout the year, beginning with its current festival, Tagwàgi, which is the name for autumn in the Anishinaabe language. The free family event is open to the public until this Sunday.

The new attraction, located on the traditional unceded territory of the Algonquin Nation, is building on the growing interest in farm-to-table culinary experiences and authentic cultural experiences told from an Indigenous perspective. The farm is also home to four Ojibway spirit horses, a rare breed that once roamed freely across the region before nearly becoming extinct.

“We definitely have different uses and visions for the farm but, first and foremost, we’re about creating opportunities to bring Indigenous people and other Canadians together,” said Mather-Simard in an interview.

Mādahòkì means “to share the land” in Anishinaabe. “For us, it’s about sharing the land with our community but also about welcoming everybody, from all walks of life, to understand how we live in harmony with the land.”

As well, the farm will serve as a gathering place to keep the conversations going and for visitors to gain a deeper understanding of Indigenous culture, she added. “I really feel strongly that everything we do here is a very small part of that Truth and Reconciliation process.”

Catherine Callary, vice president of Destination Development for Ottawa Tourism, believes Mādahòkì Farm has a bright future. “It’s so brand new that it’s not on people’s radar yet but it has the potential to become an important urban Indigenous experience,” said Callary.

“Trina is very much a trailblazer in terms of Indigenous tourism experiences in this area. She’s really established herself as someone with a great deal of vision, someone who really understands the value of strategic partnerships and collaboration in order to achieve her vision.”

As well, Callary lauded Mather-Simard for being an inspiration and role model for others. “Trina is someone who is so dedicated and gives so much of her time and energy and her vision to improving tourism, not just for herself but for her whole community.”

Mather-Simard is a member of the Curve Lake First Nation near Peterborough. Growing up in the Toronto suburb of Oshawa meant she wasn’t necessarily connected to that side of her heritage. “I think that’s really a challenge for a lot of urban Indigenous people,” she said.

She was introduced to Ottawa on a school trip and loved the area so much that she returned to study at Algonquin College. Her first job was special events coordinator for the Odawa Native Friendship Centre. She next worked for First Nations Communications, which sent her to Calgary to attend an Aboriginal Tourism conference there. It opened her eyes to the possibilities.

“I was just so blown away,” Mather-Simard recalled. “I couldn’t believe all of the great Aboriginal tourism experiences developing across Canada. I came home and said, ‘We need to be doing this in Ottawa’.”

Mather-Simard launched her tourism business in 1998 as a way of highlighting the diverse cultures of Canada’s Indigenous communities. She was in her early 20s at the time.

“When the company started it was literally me, a computer and a phone,” said Mather-Simard, who began reaching out to local events, such as the Canadian Tulip Festival and Winterlude, and working with them to add Indigenous programming. “It just kind of grew from there.”

The secret to her success, she said, has been hard work. “I think, like any entrepreneur, it was many years of long days and little pay and lots of vision, and surrounding myself with great team members who share my vision and my passion.”

She’s also faced hardships, such as two separate arson attacks that destroyed parts of her Indigenous cultural attraction on Victoria Island, including a long house, cultural displays, artwork and regalia.

As a founding board member of the Ontario Indigenous Tourism Association and as the founding board chair of the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC), Mather-Simard promotes Indigenous experiences that are the real deal.

“I’ve always been a strong believer in our community taking that lead and identifying authentic Indigenous tourism, which, in my mind, is owned, managed and the content and stories are all originating from an Indigenous person and perspective, and that it is the Indigenous community that’s benefiting.”

The company generates revenue in various ways, including consulting and event management services contracts. Funding for programming across all its events also comes from government sources, including annual grants from Canadian Heritage, Tourism Ontario, Ottawa Tourism, as well as arts organizations at the national and provincial level.

Mādahòkì Farm is working toward financial self-reliance through business incubators, agriculture production and tourism revenues.

Before the pandemic, Indigenous tourism had been the fastest-growing sector in Canadian tourism, increasing by 23.2 percent between 2014 and 2017, compared with a 14.5 percent increase in overall tourism in Canada, according to ITAC. International travellers were identified as key to the sector’s success.

“In general, tourism has been very, very hard hit and Destination Canada’s latest research says that it will probably be 2024, 2025 before we start to see a full recovery in tourism,” said Callary. “Because of the nature of Indigenous tourism and because of the market that the Indigenous tourism experiences had been really building themselves on, it’s even hit them harder.”

Yet, Ottawa Tourism believes there are better days ahead for the sector, once it starts to recover and rebuild. It has launched with Algonquin College an Indigenous tourism entrepreneurship training program. “We’re very, very strong believers in the opportunity that is here, especially on Algonquin territory, to have these fascinating, authentic and real experiences that are conducted and offered by Indigenous operators,” said Callary.

caroline@obj.ca