Every year or two, Ottawa residents are treated to a feat of modern engineering as construction crews replace an aging bridge spanning the Queensway over the course of a single weekend.

Using a process known as rapid bridge replacement, workers construct a new bridge near the existing one. Once complete, they quickly demolish the old bridge before slowly moving the approximately 600-tonne new structure into place.

This is an innovative and efficient approach that allows the highway to reopen to vehicles quickly. But what are we, as a city, getting?

(Sponsored)

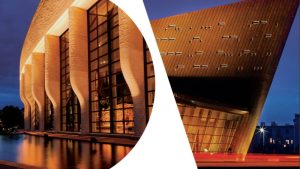

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

Borden Ladner Gervais LLP and partners lead with generosity

Borden Ladner Gervais LLP (BLG) are no strangers to supporting charities in the nation’s capital. From the Boys & Girls Club of Ottawa to Crohn’s and Colitis Canada to the

We typically get a new bridge that is, for all intents and purposes, the same as the old bridge. Sure, it’s new and hopefully lasts as long as the previous bridge.

But is it an improvement? Is the new bridge aesthetically attractive? Is it safer? Does it improve our shared urban environment?

There’s growing recognition that well-designed buildings create more liveable cities. But the value architects can deliver through their involvement in modern urban infrastructure is often overlooked.

Vanier Parkway overpass

Just east of the Rideau River, four lanes of traffic flow above Highway 417 across a relatively new bridge at the end of the Vanier Parkway.

While the province replaced this bridge just four years ago, signs of the previous structure remain. Slip lanes – the technical term for the guarded turn lanes that allows motorists to make a right-hand turn without entering an intersection – were added to the area in the past, leaving the broken remnants of the original road.

They’ve been maintained, even though we know slip lanes are hazardous and the city’s own guidelines state that “right turn slip lane designs are viewed as a negative.”

Sure, you can argue that this is a highway on-ramp, and cars need the slip lane to get up to speed. But we’re sacrificing pedestrian and cyclist safety for the incremental effect on a driver’s ability to take a corner quickly and zoom from 60 km/h to highway speed.

The sidewalks on the new bridge are about the same width as the old. They are about a metre wide, which doesn’t meet the standard for new sidewalks. The painted bike lanes that were an afterthought on the old 1950s-era bridge were replaced with – wait for it – new painted lane that looks like a bike lane, but tapers off to nothing, and a “walk your bike” sign that forces cyclists to share a high-speed road and negotiate across slip lanes.

The guard walls of the bridge are solid concrete barriers, with no articulation, decoration or sense of beauty. The lighting is a row of standard metal lamp posts. The sidewalk has already buckled, creating unsafe walking conditions that violate accessibility requirements.

The bridge is, in a nutshell, a purely utilitarian design. It meets the minimum functional design for drivers with, seemingly, no thought to anyone else, and no thought to long-term value for the community.

You could argue that there aren’t very many pedestrians or cyclists on the bridge, so why spend money to make it better for them? As Brent Toderian, the founding president of the Council for Canadian Urbanism, once said, “It’s hard to justify a bridge by the number of people swimming across a river.”

Building a better city

So, what could have been done differently with the Vanier Parkway overpass?

For starters, the slip lanes could have been removed or altered to make the pedestrian and cyclist routes safer. The sidewalk could be wider, and incorporate a separated bike lane.

The bare concrete walls could have been articulated to improve the aesthetic appearance and sense of place, incorporating pedestrian friendly lighting, landscaping or other features. And the lane widths could be narrowed, decreasing speed for vehicles and making the road safer for everyone.

These are just some of the ideas, presented in hindsight. Imagine what could have been thought of if an architect was at the table from the beginning, much as provincial legislation – albeit passed after the Vanier Parkway overpass was replaced – requires of all infrastructure projects.

Here is where design matters.

When architects are at the table, we bring ideas, innovations and holistic thinking to the discussion. We work with all parties to help make our urban environments beautiful, functional and safe for all. We show that architecture matters because all of us are affected by our built environment.

From bike lanes to buildings, design matters.

Toon Dreessen is president of Ottawa-based Architects DCA and past-president of the Ontario Association of Architects. For a sample of Architects DCA’s projects, check out the firm’s portfolio at bit.ly/DCA-portfolio. Follow @ArchitectsDCA on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram.