Crow Smith greets the deliveryman to unload a pile of packages from his truck.

The parcels and padded envelopes, many likely to contain holiday gifts, are loaded onto a trolley and rolled to the front of the warehouse.

There, they will be sorted alphabetically and placed on shelves until the Canadians who ordered them drive south down Hwy. 416 from the Ottawa area and cross the border into Ogdensburg, N.Y.

(Sponsored)

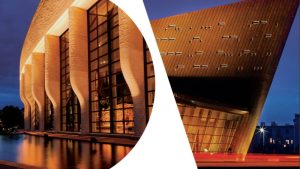

Iconic spaces, lasting impressions

The Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum offer more than beautiful spaces; they provide meaningful settings celebrating heritage, culture and design. An architectural landmark overlooking Parliament Hill

SnowBall 2026: A premier networking event with purpose returns to 50 Sussex Dr.

As winter settles in across the capital, one of Ottawa’s most high-profile charitable and business networking events is set to return to its roots: On Wed., March 4, 2026, The

Canadians have been increasingly shopping online, but scoring deals from U.S. retailers and getting them shipped right to their home has always been difficult, costly and sometimes impossible.

One reason is Canada has set its de minimis threshold – the maximum value of an item that Canadians can order from a foreign country without paying duties or taxes – at $20, which has not increased since 1985 and is one of the lowest in the world.

So people order packages to the U.S. instead, hoping to save sales taxes, customs duties and the brokerage fees they’d incur for items worth more than that.

“It ends up being a big saving,” said Smith, the owner of NAC Logistics, located just around the corner from the international bridge.

But there could be changes coming.

This summer, Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. trade representative, made it clear that he wants Canada and Mexico to raise their thresholds when he released his negotiating objectives for the new North American Free Trade Agreement.

The current de minimis threshold for American customers ordering items from other countries is US$800.

Smith, 79, has been in the cross-border shipping business one way or another for the past six decades, but since 2010, a small corner inside one of his three warehouses in Ogdensburg has been devoted to the smaller parcels that Canadians order online.

This is set up through a delivery network called Kinek, which has 134 similar locations in the U.S., mainly in towns close to the border.

It is hard to determine the impact raising the de minimis threshold would have on services like the one run by NAC Logistics.

On the one hand, it seems few people would bother with the 100-kilometre drive if it was easier to get it to the doorstep.

“There would really be no need to pick it up across the border if you didn’t have to pay duties, taxes or brokerage fees,” said Christine McDaniel, a senior research fellow with the Mercatus Institute at George Mason University in Arlington, Va.

As things stand right now, making a trip across the border does not necessarily mean saving on taxes and duties – you have to stay at least 24 hours to qualify for an exemption of $200. That exemption climbs to $800 if you stay 48 hours or more.

The Canada Border Services Agency said it does not track how many Canadians are asked to pay duties and taxes. But it collected about $54,000 in duties and just over $2 million in sales taxes at the Prescott port of entry in 2016.

Also, if the product is manufactured in the U.S. or Mexico, then NAFTA means it is exempt from duties anyway.

The real issue for consumers is that parcel delivery services charge brokerage fees for any item worth more than $20 to help figure it all out.

“Sometimes the brokerage fee, as a percentage of the share of the total value of the parcel, far exceeds the tax and the duty combined,” said McDaniel, who co-authored a report for the C.D. Howe Institute last year that argued raising the de minimis threshold would benefit consumers, businesses and the coffers of the federal government.

Dave Bucholtz, vice-president and chief compliance officer for Pacific Customs Brokers Ltd. in Surrey, B.C., said that unless health, safety and security concerns came into play – such as when consumers order medical devices or agricultural products – then brokerage fees would be unlikely to apply for anything valued under a new threshold.

Canadian retailers, many of them represented by the Retail Council of Canada, have been pushing back strongly against the idea.

“We don’t want the conferral of a tax and duty advantage on our parcel-shipping competitors operating from outside Canada,” said Karl Littler, vice-president of public affairs for the Retail Council of Canada.

Chloe Luciani-Girouard, a spokeswoman for Finance Minister Bill Morneau, said the Liberal government is “broadly supportive” of making it easier for things to cross the border, but the suggestion to waive duties and taxes needs to be met with caution.

“We need to carefully consider the impact that would have on Canadians and Canadian businesses, not to mention economic and administrative considerations for both the federal and provincial governments,” she wrote in an emailed statement.

Smith, who said the parcel service accounts for between 20 and 30 per cent of his business, did not seem too concerned.

“The main reasons customers use here is because it gets here quicker and cheaper and if they’re able to ship it into Canada, if they can ever get those mechanics ironed out where it goes up there as efficiently, time-wise, and cost-wise, then it certainly would affect us,” he said.

But there are many U.S. companies, especially smaller businesses, that will not ship to Canada for any price, because they do not think the market potential is big enough to bother with the paperwork, he said.

Besides, he said, there is something that affects his business in a much bigger way.

“The exchange rate absolutely affects us,” said Smith, adding that 2014, when the Canadian dollar was nearly at par with its U.S. counterpart, was a banner year, although things have been slowly climbing back up to that level. “People have got numb to it, I guess.”